By Mazen Iwaisi, CBRL Travel Grant recipient and PhD Candidate at Queen’s University Belfast

Archaeology does not always engage directly with scholars in other disciplines such as politics, governance and law, although the possible implications are often discussed. By breaking the disciplinary boundaries between archaeology and politics, my research analyses the concept of politicising space as it applies to landscape archaeology in Palestine in the Oslo Period (1993-2015), when Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) signed the Oslo Accords.

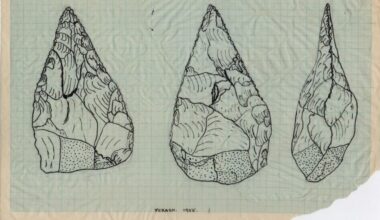

Through two focal directions of research, I aim to identify structural mechanisms that influence state and non-state actors’ decision-making on archaeological activity in the West Bank. The first refers to the discipline’s production of knowledge. This aspect has been challenged and criticised as the on-going Israeli occupation of Palestine plays a substantial role in shaping the conditions, space and time in which archaeological knowledge is produced and used. The second direction focuses on the explicit archaeo-political approach and interrogates the absence of a theoretical criticism in this regard.

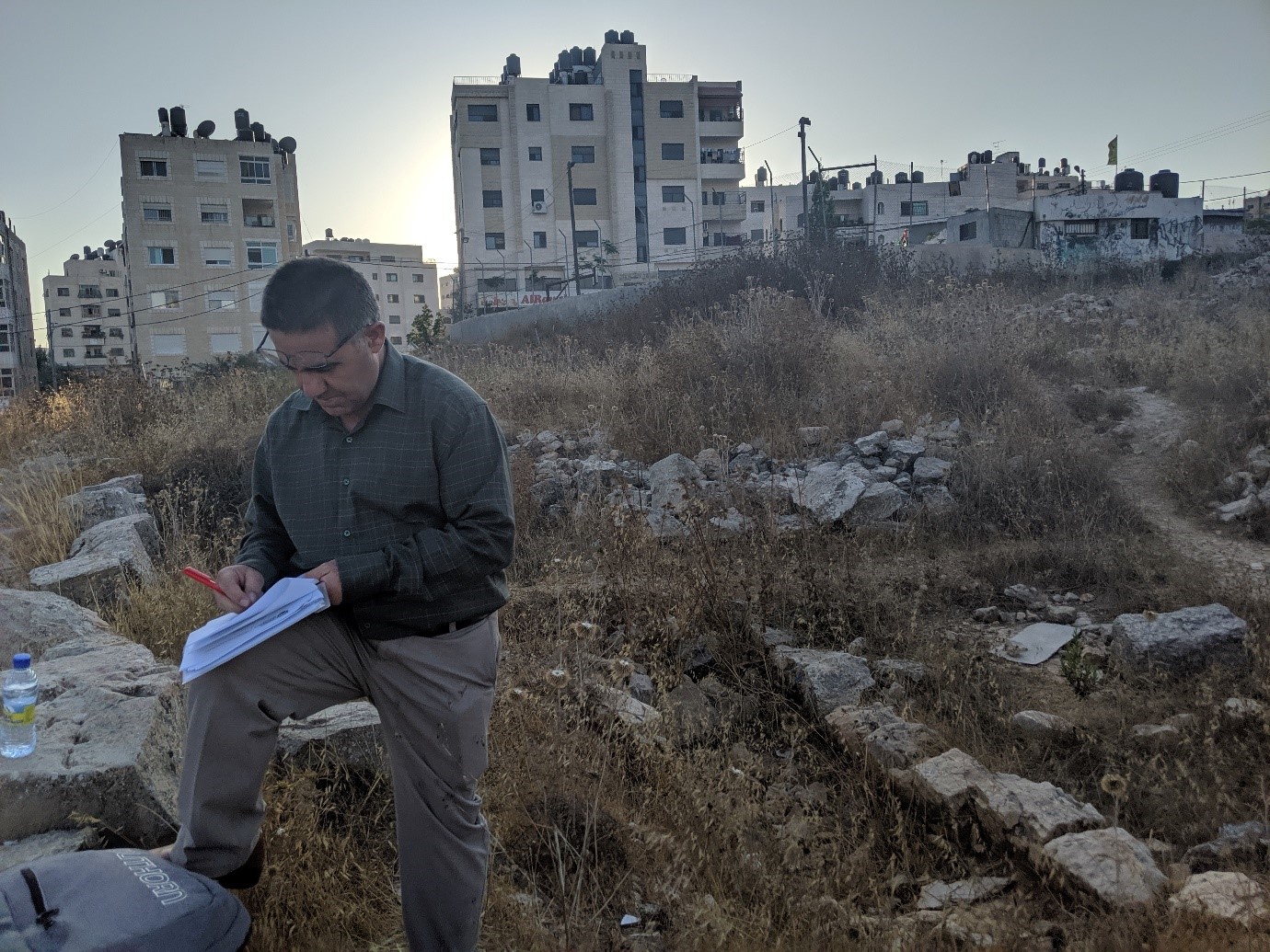

In the summer of 2019, thanks to a CBRL travel grant, I travelled to Palestine to carry out the final stages of the data collection, the ethnographic enquiry and visits to the chosen archaeological sites. Undertaking research in and on territory characterized by military occupation and complex protracted civil conflict is an endeavour prone to various obstacles. For example, I found no easy means to collect data such as journals, periodicals, international organizations’ reports, international donors’ financial reports, etc. A realistic reflection on what might be achieved and what might not be essential is required, along with a plan for alternative paths. The influence of gatekeepers is crucial where restriction and diversion are based on day-to-day routine. Significant periods of time spent “hanging out” in the areas of enquiry could be of help in developing legitimacy as a researcher in these cases.

In this context, interviews with Palestinian archaeologists and spatial planners served as a consolable source of information, touching on contemporary issues and archaeological projects that have not been covered in written secondary resources. Visits to archaeological case sites and interviews provided a clearer understanding of the current progress of archaeological park projects. They also highlighted the challenges, aspects of management and the future planning projects for sites across the West Bank. The archaeological sites’ management policies are located within the Palestinian National Spatial Plan (PNSP) and its inclusion into my research was crucial for interrogating the potential impacts on directing the development strategies and geographical distribution for economic and social activities on archaeology.

The discussions with different stakeholders centred on how PNSP spatial policies for landscape areas and archaeological sites (such as protection plans, land ownership and construction regulations) are affecting current archaeological agendas. The interviews questioned the governance modalities over private land ownership that contains archaeological sites and how future planning might impact those sites. The archaeological site of Tell el-Tell near Ramallah for example, illustrates such a case of ongoing disputes over land ownership. The site covers 139 dunums in size. According to the Approved Urban Master Plan of the area, in this specific area, a dunum is worth a quarter of a million US dollars. With the Palestinian Department of Antiquities’ current plans to transform the site into a national archaeological park, several landowners have agreed to the Department’s vision and are willing to give up their land given the appropriate compensation. However, others remain reluctant to any kind of settlement and are demanding the absolute right to dispose of their property.

At the end of my fieldwork and ethnographic enquiry, a half-day multi-disciplinary workshop was organized in Ramallah with a group of young Palestinian scholars in cultural landscape. The participants discussed and provided valuable strategies to overcome challenges that the PNSP is facing, especially in area C of the West Bank, which is under Israeli civil and military control and makes up some 60% of the West Bank. One of the key conclusions that arose from my fieldwork was that involvement of local communities is crucial in creating a space that respects local traditions and meets the needs of local inhabitants. Their opinions, concerns and interests are not simply relevant as the targeted audience, but decisive for the success of the projects.

The participants also discussed inclusion, grassroots and community outreach that are fundamental aspects in contemporary cultural resource management (CRM) engaged archaeology theories and practice. These approaches intersect with other disciplines like politics, governance, management, law. Despite the rise in popularity of CRM worldwide in the last decade, participants highlighted the significant deficit of such approaches in countries in the Middle East, particularly in Palestine. The young scholars reflected on their experience and contribution to encourage the local community to design a bottom-up approach, rather than promoting an elitist agenda. There was a focus on how to create a long-term impact programme in these villages and their landscape where cultural heritage is vulnerable to destruction and looting due to the high rate of unemployment in these villages.

As a general conclusion, archaeological projects must be shaped in collaboration with local practitioners that are familiar with the local reality and the challenges faced by these communities. This can only be done by means of an integrative approach, that navigates across disciplines and builds on the multifaceted environment. One of the long-term recommendations that may contribute to overcoming some of these issues, is to create living cores in the old centres of villages to act as stimulating hubs for further creativity and development.

Mazen Iwaisi is a PhD candidate at Queen’s University-Belfast, his research study – Landscape Archaeology as Politicised Space in Palestine – is an interdisciplinary project binding together politics and archaeology. Mazen is a researcher is landscape studies and has been involved in several archaeological surveys, excavations, and landscape archaeology projects in Palestine. His research focuses on identifying the structural mechanisms that influence the decision-making of state and non-state agents in archaeological activities in Palestine on the issues of selection, governance, imagination and power.

The views expressed by our authors on the CBRL blog are not necessarily endorsed by CBRL, but are commended as contributing to public debate.