By Kamal Badreshany and Graham Philip, Durham University

Since 2015, the American University of Beirut (AUB) and Durham University have worked together on an exciting new archaeological project at Tell Koubba in Northern Lebanon . Tell Koubba is located 60km north of Beirut, at the point where the Wadi Jawz, one of the main watercourses of north Lebanon, enters the Mediterranean Sea. The village of Koubba occupies a dramatic position along the southern edge of the Ras Shiqaa formation (figure 1). This rocky outcrop dominates the area to the north and contains numerous natural caves and springs, which, in combination with good arable land, has drawn people to the area for millennia.

Tell Koubba has turned out to be an excellent site for the study of the development of complex societies, a favourite theme for archaeologists, allowing a better understanding of the unique development of societies in coastal Lebanon.

Koubba I

Tell Koubba includes two main sites, Koubba I and II. Tell Koubba I, a low mound with an area of roughly 5 hectares, is one of the few well-documented Neolithic sites in northern Lebanon. It provides a substantial amount of archaeological material which sets the site apart from earlier excavations of coastal settlements, for many of which samples either of fish or bird bone and plant remains were not collected. The wealth of findings at Koubba provides a valuable window on life in early farming communities on the Mediterranean coast.

The site was cut by a railway, constructed in haste during World War II (when Rommel’s army was threatening the vital harbour at Alexandria). Two long vertical sections are exposed in the sides of the railway cutting. Copeland and Wescombe (1965: 101) visited the site in the 1960’s and reported mainly Neolithic and Chalcolithic remains.

Several seasons of work, including soundings and systematic surveys of the immediate area, have produced a substantial amount of material, including a rich botanical assemblage, Palaeolithic hand axes (figure 2), a large assemblage of Neolithic flint and obsidian tools (figure 3), a small figurine (figure 4), a wide range of Neolithic (figure 5) as well as later Early Bronze Age II (EBA II) ceramics. The material excavated belongs to what is called the Pre-Pottery Neolithic C (PPNC). This term is applied to sites that produce chipped-stone tools of types common in the Ceramic Neolithic but have no pottery. As pottery appears earlier in north and west Syria than it does in Palestine and Jordan, sites assigned to the PPNC are most common in the southern parts of the Levant. Koubba therefore represents an unusual northern instance of this phenomenon, and our eagerly-awaited radiocarbon dates will allow us to place the PPNC of north Lebanon in time.

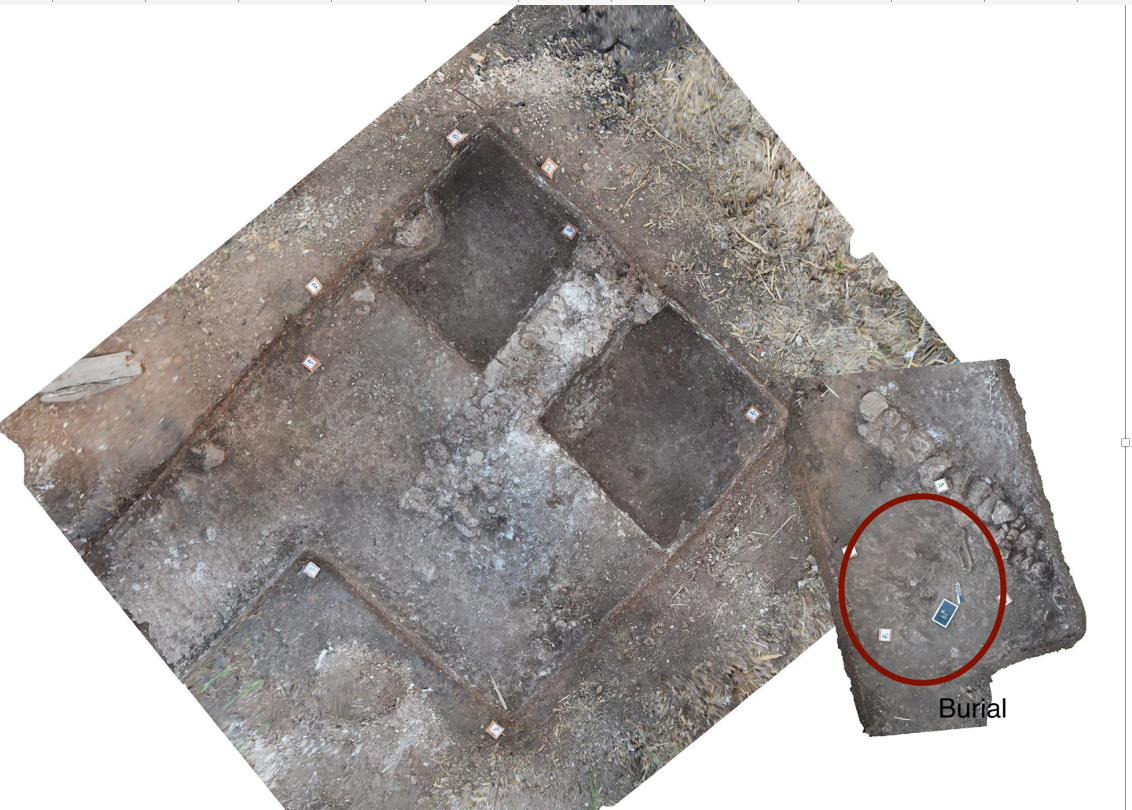

The stone foundations of a Neolithic structure were uncovered during the 2017 and 2019 seasons at Koubba I. The walls were preserved to a width of 80cm and a height of 60cm, and the evidence shows the building was large – at least 7 by 5 meters (figure 6). The uppermost floor of the building is unusual, as it is made using chalk discs embedded in mud. We suspect that this was intended as a low-cost substitute for the ‘genuine’ lime-plaster flooring which was popular during the Neolithic.A largely intact burial was found resting against the building’s northern wall (figure 7). It contained numerous carefully placed domesticated animal bones, including sheep goat, cow, and calf. The deceased was laid in a crouched position, one hand was missing and was replaced by the skull of a sheep or goat. In the other hand, which was placed near to the face, the deceased held a disc of chalk/plaster, identical to those used to construct the floor.

Koubba II

Tell Koubba II is located about 500 meters to the east of Koubba I, and is mostly of EBA III date (2800-2550 BC). The upper part of the site was located on a spur of Ras Shiqaa giving great views over the valley to the east and south, and commanding the main north-south route through the Shiqaa formation. The shift in location from Koubba I, oriented towards the coast, to Koubba II – further inland and higher up – at the end of the EBA II (early third millennium), suggests a growing interest in control of movement, perhaps itself linked to an increasing flow of commodities around the landscape.

Archaeological remains are preserved along the lower slopes of Ras Shiqaa with large fragments of pottery visible at the edge of a road cutting. In 2016, we found four large, fully restorable, ceramic vats each placed upon a stone setting (figures 8 and 9), the first such find for the Early Bronze age of the Levantine coast. The vats were situated in a building that also contained a circular stone structure, with channels leading between rooms. The building belongs to the latest occupation of this part of the site and it seems to have been used for the large-scale processing of olives and grapes. This hypothesis is supported by the charred plant remains found at the site that, together with the animal bones found, provide a picture of daily life at Koubba II during the Early Bronze Age. The plant material is dominated by olive pits and grape seeds – which with the vats and jars all point to a specialised economy, perhaps producing tribute for a larger centre at Byblos – about 20 km to the south along the coast.

In 2017, we realised that the vats and the circular silo base had been in use during the latest phase of a monumental wall, probably part of an enclosure or boundary wall, more than 1m thick and standing seven courses high (figure 9). We have so far uncovered 19 metres of the wall and it continues to the west. At its eastern end, the wall ends with a bastion faced with neatly dressed stone blocks (ashlars).

Excavation inside the wall revealed rich deposits of domestic refuse, including several restorable vessels which allowed us to gain a better understanding of the shape, size and volume of EBA pottery. The first purpose-built transport jars appear in the EBA suggesting the existence of inter-regional economic links. In fact, vessels from Lebanon have been found at Old Kingdom sites in Egypt, where Lebanese commodities such as olive oil, wine and timber were in demand. Another unique aspect of Koubba II, for EBA Lebanon, is the presence below the main tell of a lower settlement, that extends across the fields towards the Wadi Jawz. Geophysical prospection in this area indicated the presence of structures below the plough soil, coinciding with concentrations of EBA pottery – brought to the surface by ploughing. A test trench dug in 2019 revealed lots of stone, probably from disturbed buildings, and numerous sherds from vats and jars which suggest that the area was used for the processing and storing of agricultural produce, olive oil in particular.

The excavations at Koubba show that the development of Lebanese ancient societies followed very different trajectories from those known from Palestine, Jordan and Syria. These areas have so far received greater scholarly attention than Lebanon. To fill this gap, archaeological explorations will need to focus on the fertile valleys and basins of the Lebanon mountain range, which lies to the east of Koubba.

Acknowledgements

Tell Koubba is excavated by a joint project of the American University of Beirut and Durham University directed by Prof Hélène Sader, and authors Badreshany and Philip, with support from the Council for British Research in the Levant, and the Society of Antiquaries of London. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Directorate General of Antiquities of Lebanon who kindly gave permission to excavate at the site.

Kamal Badreshany leads the Durham Archaeomaterials Research Centre (DARC), an analytical research facility based in the Department of Archaeology that offers advanced chemical and materials analysis for academia and industry. He received his PhD from the University of Chicago in 2013. His research focuses upon human adaptation to changing social, economic, and environmental conditions, especially as related to increasing settlement density and the formation of the earliest states in the Levant. He specialises in the analysis of archaeological materials using archaeometric techniques, including ceramic petrography, scanning electron microscopy, XRF, ICP and X-ray diffraction, and he has published extensively on the role of ceramics in the ancient Levant.

Kamal Badreshany leads the Durham Archaeomaterials Research Centre (DARC), an analytical research facility based in the Department of Archaeology that offers advanced chemical and materials analysis for academia and industry. He received his PhD from the University of Chicago in 2013. His research focuses upon human adaptation to changing social, economic, and environmental conditions, especially as related to increasing settlement density and the formation of the earliest states in the Levant. He specialises in the analysis of archaeological materials using archaeometric techniques, including ceramic petrography, scanning electron microscopy, XRF, ICP and X-ray diffraction, and he has published extensively on the role of ceramics in the ancient Levant.

Professor Graham Philip obtained his PhD from Edinburgh University in 1988, and worked as Assistant Director of the British Institute at Amman for Archaeology and History (1989-1992). He was a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the Institute of Archaeology, University College, London, before taking up a lectureship at Durham University in 1994. His research interests fall into three main areas: landscape archaeology, artefact studies, and the nature of early complex societies. All of these themes are explored in the context of the later Prehistory and Bronze Ages of the Middle East. Prof. Philip is currently a Co-I on the heritage protection project Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa, working with project partners in Lebanon, Iraq and the Caucasus, and co-directs with colleagues at Yarmouk University, a project to create an environmental isoscape map for Jordan, funded by an AHRC-Newton award.

Professor Graham Philip obtained his PhD from Edinburgh University in 1988, and worked as Assistant Director of the British Institute at Amman for Archaeology and History (1989-1992). He was a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the Institute of Archaeology, University College, London, before taking up a lectureship at Durham University in 1994. His research interests fall into three main areas: landscape archaeology, artefact studies, and the nature of early complex societies. All of these themes are explored in the context of the later Prehistory and Bronze Ages of the Middle East. Prof. Philip is currently a Co-I on the heritage protection project Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa, working with project partners in Lebanon, Iraq and the Caucasus, and co-directs with colleagues at Yarmouk University, a project to create an environmental isoscape map for Jordan, funded by an AHRC-Newton award.

The views expressed by our authors on the CBRL blog are not necessarily endorsed by CBRL, but are commended as contributing to public debate.