Interview by Minying Huang.

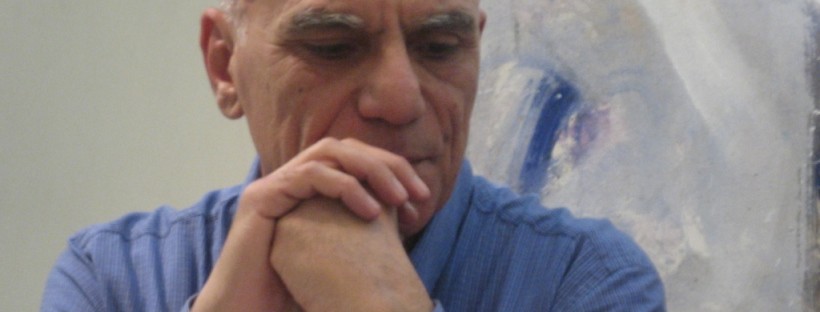

Ibrahim Samuel is a Syrian writer and journalist living in Amman, Jordan. He has published five short story collections, and some of them have been translated into Italian, French, Bulgarian, and English. His work orbits around political themes such as oppression, freedom, cultures of silence, and dictatorship and its effects. He has previously been featured in Banipal Magazine of Modern Arab Literature (UK). Bleu Abrupt, his most famous book, is available in French here on Amazon.

This interview has been translated from Arabic into English.

How did you get into writing?

I have loved the art of the short story ever since I was little, from about the age of 13 or 14 onwards; but it was only when I turned 17 that I really began to think about writing one myself. And so then I actually sat down and wrote a story titled The New Robe (1968). I sent this piece to the Syrian newspaper The Revolution, and to my complete surprise they published it. This was one of the happiest moments in my life. But I didn’t know then that I wouldn’t write another story until 1986. For a long while, I was just trying to read as much as I could and, embroiled in the battle of life, I was also investing all my time in working to achieve freedom and democracy in my country. I was arrested twice on account of my political activities, in 1977 and 1986. During my second stay in prison many ideas for short stories came to me. When I was released, I found the time to write down these stories, and they were published in 1988 in a volume called Scent of the Heavy Step.

Do you think that writing is a necessarily political act?

In short, yes. All writing is political expression, even if there is an absence of terminology. In the words of the great Egyptian writer Mahmoud Amin al-‘Alim, the simple act of being human is a stance.

How do you think the number of expatriated Arab writers in Jordan has affected the literary scene here?

Without a doubt, it has had a significant impact on the literary scene here. And Jordanian writers know this. Certainly, expatriated Arab writers do not feel foreign or alien here because this country is like a second home to us; and the people of Jordan are our people as well. Much of the literary output in Jordan consists of books by Iraqi, Syrian, and Palestinian writers, and, truly, these books have contributed to the enrichment of the cultural and literary landscape in Jordan.

Which writers have influenced your life and your work?

So many writers – Arab and non-Arab – have influenced my life and my culture and my writing. But among them the most influential are: the Russian writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky and the Egyptian writer Yusuf Idris. I feel that their work is tattooed in my soul, my heart and my mind, and I’ll never forget how much they inspired my love of writing and what I write.

What are your thoughts on promoting dialogue and understanding between the Arab world and Europe? What are the obstacles to intercultural exchange, and how can we overcome them?

Several cultural bridges need to be built between the Arab and European peoples so as to foster empathy, understanding, and cooperation – so that humanity can live in peace. A major obstacle, for sure, lies entangled in politics. And we should also look at the role played by governments, institutions, and cultural centres in both regions. Isn’t it strange that similar obstacles do not stand in the way of commercial trade and tourism, whilst so many barriers exist to prevent the realisation of real cultural exchange?

As for the need to dismantle these barriers, really, this can only happen if both sides are sincere in their desire to overcome the obstacles.

Do you have a personal or professional connection to the UK?

Sadly, no. Some of my stories have been translated into English. However, this happened inadvertently and in such a way that I didn’t even know that I had been published in Banipal until you told me and showed me my contributor profile.

Is there an audience for socially-conscious art here? How can we draw attention to the Jordanian literary scene and attract a wider readership?

Of course, throughout time, and across societies, there has always been an audience for more reflective art and an audience for light consumer entertainment. As for attracting a wider readership, this is not only dependent on the writers themselves, but also on various bodies, institutions, and departments, and on various community services and facilities. This makes it difficult to narrow it down to one answer and determine the best course of action.

Western critics have, unfortunately, sometimes been known to exploit Arabic literature to portray the Middle East in a negative or distorted light. Does this make Arab writers wary of the possibility of their work being misrepresented?

The story of the relationship between the Arab East and the West is, generally, a complicated one, both historically and at present. It’s regrettable that in the past few years the narratives on both sides have grown increasingly complex and interwoven, and to evaluate and rectify the situation would require a tremendous amount of effort and a genuine will to do so. This does not seem to me to be on the near horizon – and that’s assuming the intention is there in the first place.

Can you detail your creative process?

I can’t pinpoint where it starts exactly. A look, a word, a scene, a movement, a facial expression… a constellation of small details of which every detail formed is a matchstick to ignite an idea in its entirety, or illuminate it, or bring it into being. There is a period of development, then toil, culminating in the birth. What I want to say is that I never write with a fixed idea in my head. The story is born – or not born – as it sees fit, and I am unable to intervene in the timings of its manifestation, nor in the window of its absence.

Most of your stories – though not all of them – are left open-ended, with multiple possibilities. What does this choice you’ve often made mean to you?

I like to leave my stories open-ended, because the endings in life always bring new possibilities and uncertainties, and because I do not go about writing my stories with preconceived endings in my head. I want the reader to have a share in the writing of the story; it might be that they fill in the gaps with the endings they envision, or perhaps they too will leave it open to possibilities, to mirror life.

Minying Huang is a student of Spanish and Arabic at the University of Oxford, who spent the year 2015-16 in Amman studying Arabic at Ifpo (Institut Français du Proche Orient). She has published blog articles for Your Middle East and Stop the Street Harassment.

The views expressed by our authors on the CBRL blog are not necessarily endorsed by CBRL, but are commended as contributing to public debate.