By Steven Wagner, CBRL centennial award holder, historian and lecturer at Brunel University London.

Before I started my book, my research focused on British intelligence on Jewish illegal immigration and terrorism in Palestine. More broadly speaking, I use multilingual and declassified records which shed new light on the story of intelligence and British imperialism in the Middle East. Those same records also impact our understanding of the Palestinian and Zionist national stories. Thanks to the CBRL centennial grant, I have recently research on the long-lost archive of the controversial Palestinian leader, Hajj Amin al-Husayni.

This new project will shed light on his wartime activity, but also the fate of the Palestinian national movement. Amin al-Husayni, Mufti of Jerusalem from 1921-37, was the key Palestinian leader during the British Mandate period. He remains a controversial subject for his alignment with Nazi Germany during the war, but before then, was a key organizer of nationalist opposition to British policy. He was also the most senior Palestinian representative in colonial government until his flight from arrest by British troops and police during the Palestinian revolt. From 1937 until 1941, Husayni led resistance abroad from Syria and Iraq before travelling to Italy and Germany. A divisive leader, many scholars attribute Palestinian failure to achieve independence to his confrontational, often murderous, politics.

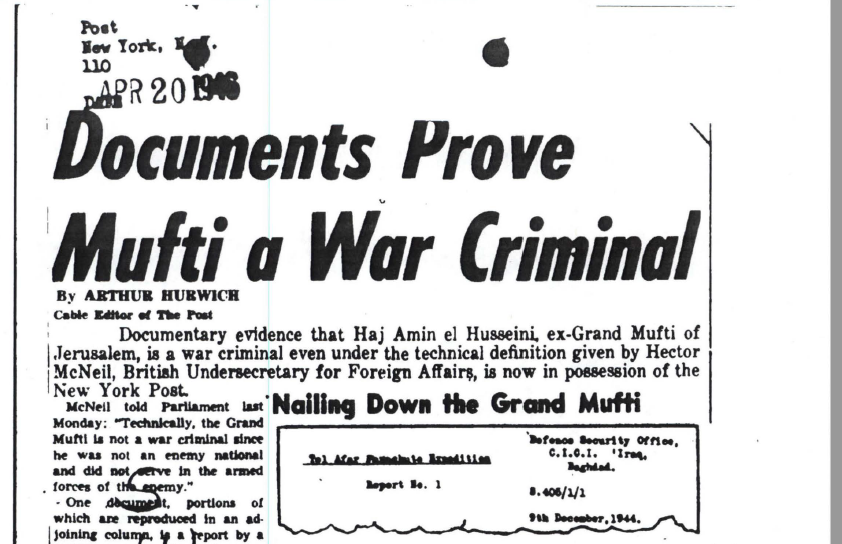

Husayni’s relationship with Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany has dominated both academic and public discourse about him. When writing Statecraft by Stealth, I strived to discuss the Mufti’s political career before the Second World War without being influenced by what we know came next. In July 1945, the United Nations War Crimes Commission listed Husayni as a war criminal on the basis of Yugoslavia’s indictment, for his role in creating Bosnian SS battalions.

In November 1945, the Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) of the US army uncovered the private archive of Hajj Amin al-Husayni in Bad Gastein, Austria. Husayni buried the materials there before attempting to seek refuge from the allied armies in Switzerland, where he was blacklisted, and forced to return to the French zone of occupation in Austria. Meanwhile, a copy of his archive was made available to Zionist intelligence, who were helping their American counterparts with an operation codenamed “Symphony”. The Mufti’s papers were leaked to journalists and activists in America who prepared anti-Palestinian, pro-Zionist propaganda aimed at the delegations to the United Nations in 1947. Since then, fragments only saw light during the Eichmann trial in 1961.

After finding references in American archives to the Mufti’s papers, I traced them to Israel archives where they still reside. Since 2016, Israeli archives have shifted toward digitization. In that process, the original Arabic letters have been made available to the public via the archive’s website, but some content, such as the index prepared by the American intelligence officer who first handled the Mufti’s papers, remain inaccessible. Since I visited when full access was possible, I possess a more complete record. Other records have gone missing – Tuvia Arazi, an old intelligence hand working for the Israeli “Foreign Ministry”, swore in 1961 that the material included hundreds of photographs, which I have not yet found.

The CBRL grant covered the translation and transcription of files covering Husayni’s correspondence with Shakib Arslan – a pan-Islamist journalist, poet, activist and diplomat. Arslan sided with Germany in both world wars. A Druze Prince by birth, but a Sunni Islamic Modernist by choice, his main goal was to strengthen Islamic societies so they could resist Christian imperialism. In Arslan’s letters to Hajj Amin, the former frequently (and helpfully) recounts what the Mufti told him in his sent letters. It is also possible to cross-check these materials with the Mufti’s diaries.

This has proved to be a most revealing aspect of the material. Compared to the Husayni’s other correspondents, Arslan was certainly the Mufti’s most honest relationship. Both seem to tell each other what they really think. Arslan was Husayni’s only surviving mentor by the 1940s. Husayni admired Arslan and looked to his anti-colonial leadership, while Arslan held Husayni in high esteem for stepping up in the struggle against the British in the later 1930s. Arslan played an important role in encouraging that step.[1]

With the help of the CBRL centennial grant, we are making translations of these materials available to researchers and the public over the coming years. This original research will stimulate new perspectives on the Mufti in both scholarly and public settings. It will also shed new light on the history of Mandatory Palestine. In particular, his honest correspondence with Arslan illustrates his ongoing efforts to lead Palestinian resistance from exile, his connections to other Palestinian and pan-Arab leaders, and his ongoing assassination campaign against Palestinian opponents and rivals.

The material provides more than primary evidence of Husayni’s criminality. The archive offers context, showing that that while he did not arrive in Berlin a Nazi, he certainly fled Germany as one. His correspondence reveals his pattern of alienating Arab military leaders and erstwhile comrades such as Fawzi al-Qawuqji or Rashid ’Ali al-Kilani, who led revolts in Palestine and Iraq respectively. Husayni blamed them for failure and falsely accused the former of collaboration with Britain.

These archival records are shedding important light on the most prominent Palestinian leader of the British Mandate period, adding to our understanding about the end of British rule in Palestine, the rise of Israel, and the many obstacles which faced Palestinian independence. By making these translations available digitally to researchers and the public, I hope to separate the propaganda about his Nazi connections from fact.

[1] Twice, in fact: in 1935, and again in 1937. Steven B. Wagner, Statecraft by Stealth: Secret Intelligence and British Rule in Palestine (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019), 130–33, 185.

Dr Steven Wagner is Lecturer in International Security at Brunel University London. His book, Statecraft by Stealth: Secret Intelligence and British Rule in Palestine, published by Cornell University Press, examines the relationship between intelligence, policy, and armed conflict in Mandatory Palestine.

The views expressed by our authors on the CBRL blog are not necessarily endorsed by CBRL, but are commended as contributing to public debate.