By Cat Auburn, Postgraduate Researcher at Northumbria University

In 2012, I became aware of the curious Victorian mourning practice of weaving human hair into the form of floral rosettes. Unlikely as it initially sounds, this led directly to my exploration of New Zealand World War One (WW1) narratives in the Levant.

I remember feeling both fascinated and mildly queasy as a friend described a type of fancywork no longer commonplace, but popular during the Victorian period: the mourning wreath. Women would snip a lock of hair from the head of a deceased family member and weave it into a flower-like object. This was then added to the family mourning wreath to join the hair-rosettes of other dead loved ones. These bouquets of human hair seemed to me to be visceral, tangible maps of genealogy, grief and memorial. The European tradition of hair-memento eventually hitched a ride abroad with emigrants; including to my home country, New Zealand.

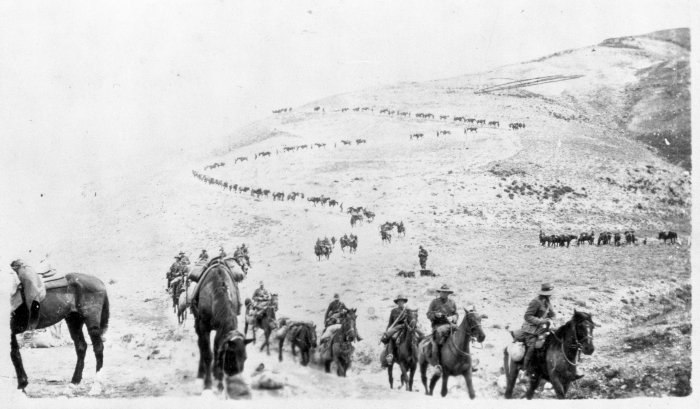

In tandem, I learnt of New Zealand’s involvement in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of WW1. This came through a story told to me by way of an invitation to visit the gravesite of a New Zealand war horse: the New Zealand government sent 10,000 horses to Egypt and the Levant from 1914-16 as part of the British war effort. In 1919, when the remaining New Zealand Mounted Riflemen were finally scheduled to leave the Levant and return home, they discovered that their horses would not be returned to New Zealand with them. In response, some men chose to kill their horses rather than leave their companions behind to an unknowable fate. Of the ten thousand horses, only four ever made it back to New Zealand.

This was a disorienting story for me. New Zealand, Australia and the United Kingdom (amongst others) were marching towards the 2014-18 WW1 Centenary Commemoration period, and I had never heard of the Sinai and Palestine Campaign. As I canvassed friends and family, it became clear that a WW1 connection to the Levant was not common knowledge to the New Zealand public. The origin story of New Zealand’s national identity has been distilled down to a birth on the battlefields of Gallipoli during the Dardanelles Campaign of 1915-16 and solidified in the mud of the Western Front. This dominant narrative obscures the diversity of New Zealanders’ experiences and memories, it largely ignores the indigenous position and completely overshadows the role of New Zealanders in the Levant.

I saw the impending centenary moment as an opportunity to question the frustratingly narrow parameters of public memorialisation. In New Zealand this commonly takes the form of traditional heroic statues cast in bronze. Despite their size and prominent position, they are largely invisible in the public spaces, which they inhabit. The effect of these singular, monolithic statues is the distillation of the WW1 experience into one homogenous, often alienating, narrative of ‘the glorious dead.’ Their static symbolism evades the complexities, contradictions and individual lived experiences of WW1.

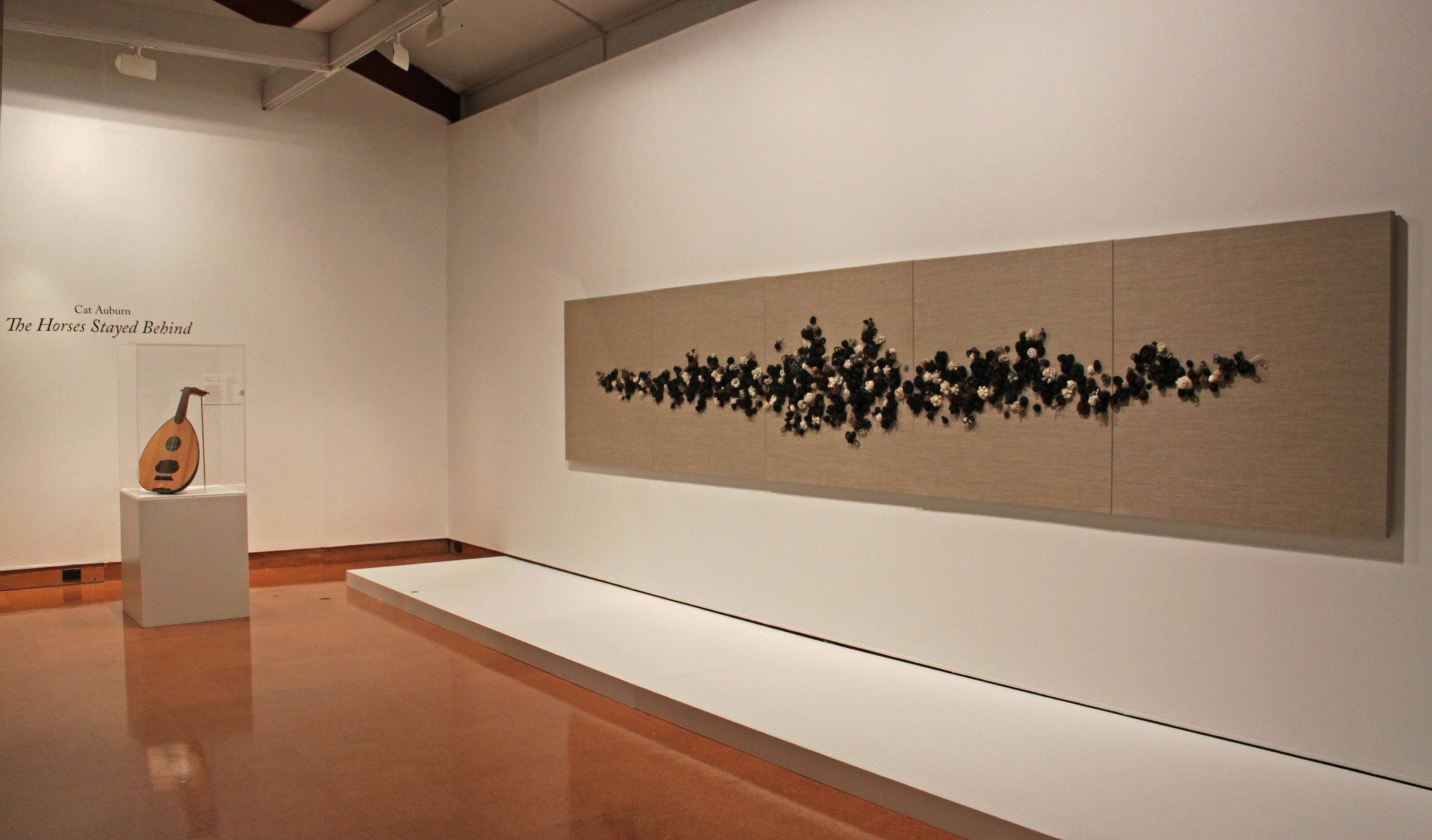

As an artist, I felt it was appropriate to explore the strangely absent narrative of New Zealand’s involvement in the Levant through sculpture; specifically, returning to the Victorian mourning wreath. The intimate, domestic nature of mourning wreaths was a welcome foil to the kind of singular, stoic remembering offered by the previous monumental bronze statues.

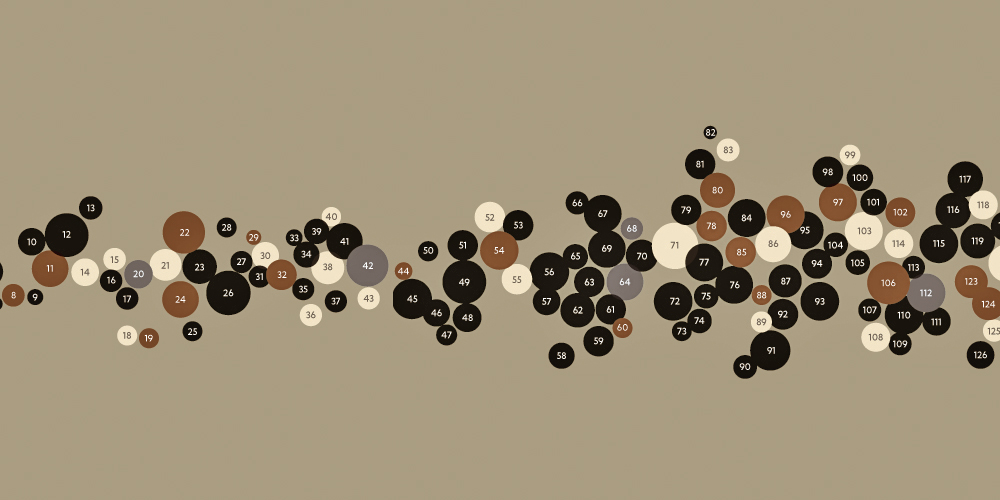

Because my interest in the Middle East Campaign of WW1 had initially been piqued by the tale of the horses, I chose to work with horsehair rather than human hair. I approached the equestrian community in New Zealand for donations of tail hair from live horses. This was the same community that had supplied the war effort with horses in 1914-18, and the offer resonated so successfully that I received hundreds of individual donations. The collection of horsehair also became a means to connect directly with the public and hold space to hear their familial histories and personal beliefs about the collective memory of WW1. These discussions enriched and shaped the project as it developed.

The resulting exhibition, titled ‘The Horses Stayed Behind’ (after a poem by Trooper Blue Gum), toured New Zealand for three years and featured: a large horsehair mourning tapestry; a middle eastern instrument called an oud, made from New Zealand horsehair and timber; a tiny fragment of bronze from a 1930s ANZAC memorial statue (now destroyed, originally located in Port Said, Egypt).

‘The Horses stayed Behind’ enabled me to engage in an artistic intervention with the traditional mechanisms of memorialisation. It is significant that many individual stories exist within the artwork, each one represented by a unique woven rosette. The donors and their horses are not anonymous – they can be identified by an infographic map that accompanies the exhibition. In this way, the artwork can be read as a collective whole without pushing an oversimplified, single truth about WW1.

Through the course of ‘The Horses Stayed Behind’, my eyes were opened to my culture’s collective inclination towards selective memory. My ancestors left Britain and Ireland for reasons lost to me; their memories and traditions were traded for anonymity and a type of intentional forgetting. This is one amongst many aspects of my colonial, psychological inheritance that I have complicated feelings about. During a workshop at CBRL Amman in 2018, I had the opportunity to further reflect on the New Zealand Mounted Riflemen’s engagement in the Levant whilst being in the region. The colonial inheritances of this engagement – in particular, its complex relationship with the colonial history of New Zealand – is the current focus of my PhD research.

I am looking forward to developing this practice-led artistic research with the cultural material of WW1 that exists in museum collections across the Middle East, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. I also plan to follow a portion of the route taken by the New Zealand Mounted Riflemen deployed in the Middle East between 1916-19, with performances of the oud created during ‘The Horses stayed Behind’ to be staged at various battle sites. Interestingly, during a reading of diary entries from New Zealand troops at a battle site in Amman as part of the CBRL workshop (2018), the exact location of the battle field was disputed. This doubt, arising from conflicting post-colonial narratives, is important to my research. In this way, the playing of the oud becomes a similar mechanism to the collecting of the horsehair – a vehicle with which to open space to explore, question, test and discuss with the audiences the specific cultural memories they hold, and to collaborate on the project as it develops.

‘The Horses Stayed Behind’ (2015) received the 2016 Award for Best Regional Art Exhibition at the New Zealand Museum Awards. The project and its national tour (2015-2018) was supported by the Tylee Cottage Artist Residency (2014-15), The Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua Whanganui (NZ) and Creative New Zealand.

Further reading:

https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-curious-victorian-tradition-making-art-human-hair

Kinloch, T. (2007) Devils on Horses. In the Words of the ANZACS in the Middle East 1916-19. Auckland: Exisle.

Mein Smith, P., 2005. A Concise History of New Zealand, Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-ReiKaOr-t1-g1-t9-body1-d4.html

Cat Auburn is pākehā – a New Zealander of European descent. She is a visual artist exploring systems of power through sculpture and film to reveal the construction of contemporary shared beliefs and collective memory. Cat is a Post Graduate Researcher at Northumbria University with the AHRC Northern Bridge Consortium (UK). Her research focuses on New Zealand’s engagement in the Middle East Campaign of WW1 and the colonial inheritances of this involvement.

The views expressed by our authors on the CBRL blog are not necessarily endorsed by CBRL but are commended as contributing to public debate.