By Simone Lemmers, CBRL Fellow at the Cyprus Institute, Nicosia

Osteoarchaeologists are interested in how people in the past used to live their lives by studying ancient human skeletal remains. Human hard tissues (bones and teeth) are extremely versatile in telling us what people in the past ate, where they grew up, where they lived, what illnesses they might have suffered from, what kind of activities they undertook and much more.

Cyprus is rich in archaeological remains and material culture, but archaeologists like me who are interested in studying human remains are faced with a challenge of conservation. Due to Taphonomy, which literally translates as ‘the law of burial’ (Greek taphos, τάφος meaning “burial” and nomos, νόμος meaning “law”), ancient Cypriot bone material is often found to be fragmentary and poorly preserved when retrieved by archaeologist from the soil. Teeth, the hardest material in the body, however often survive over long periods of time, even if preservation circumstances are unfavourable. Teeth are therefore extremely interesting to me.

During my PhD, I examined the remarkable way in which teeth can preserve detailed information of an individual’s past. When you are young and your teeth are still forming, every day a tiny layer of tooth material is formed. Normally, this is a smooth and incremental process, but stressful events such as a period of illness can leave distinct marks in the tooth, which are colloquially called ‘stress lines’. The way teeth grown and record stressful events or episodes can, in a way, be compared to the growth of trees and formation of tree rings, as explained here.

By using light microscopy, I extract these stress lines from teeth and reconstruct a story of an individual’s first years of life. During my CBRL fellowship I applied this amazing technique to ancient Cypriot teeth. My project centres around the question of what effect the urbanisation process during the Bronze Age had on the health of individuals and populations. By focussing on children and how difficult their period of infancy was, I explore this question. Specifically, the first molar is key to this research since this tooth contains a stress line formed when the person was born. We call this the ‘Neonatal line’. Once I’ve found this line inside a tooth I can then calculate the timing of other stress lines on the teeth.

The first step of this project was to locate remains from various prehistoric sites around Cyprus to select relevant samples to document (Image 1).

The Cyprus Institute curates multiple collections of human remains that I was able to work with during my fellowship. The first part of the work consists of diving into the storage room to source for the right material. On the bottom right, you can see a fragment of an upper jaw with premolars and molars of an adult person (the first molar in the middle). These are the type of teeth I selected for analysis.

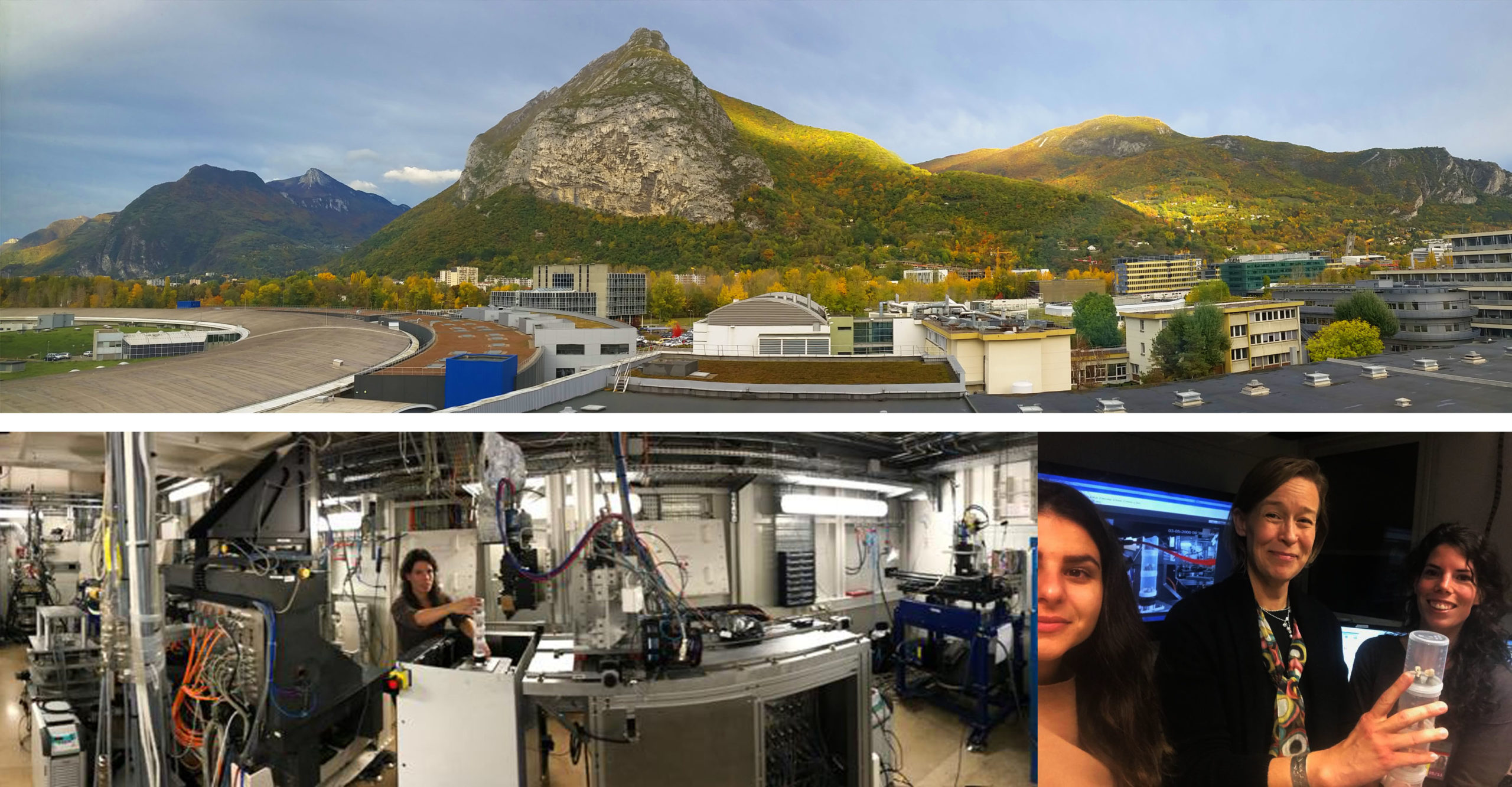

At the Science and Technology in Archaeology and Culture Research Center (STARC) in Nicosia, I worked closely with Bio-archaeologist Dr Kirsi Lorentz who introduced me to the application of Synchrotron Radiation to archaeological remains. Synchrotrons generate powerful light beams which allow us to see inside materials such as teeth with much more power than any conventional microscope. This meant that instead of doing destructive research required for the conventional way of studying the microstructure of teeth, I had the opportunity to take these specimens to one of the world’s most important Synchrotron Radiation Facilities, ESRF (Image 2). Dr Lorentz obtained access to this facility for her large project on Dental Tomography at ID19, working with beamline scientist Paul Tafforeau and I was given the unique opportunity to join her and analyse my selected Cypriot molars.

The site of ESRF is located in the mountainous valley of Grenoble, a beautiful setting. The scenery was just the tip of the iceberg: working at a Synchrotron Radiation Facility gives you access to the most advanced and state of the art technology out there. But be warned: it requires stamina! When a team is granted access to the facility, they work 24 hours a day and multiple days in a row to make the most of the time that they have there. Our team from the Cyprus Institute included Principal Investigator Dr Kirsi Lorentz (middle), PhD student Grigoria Ioannou (left) and myself. The first results of our analysis look very promising, so the long days in the lab are absolutely paid off!

In addition to my own CBRL project on ancient teeth, I have joined Dr Lorentz on one of her projects on bone preservation at SESAME, the Synchrotron of the Middle East, located in Jordan. SESAME (Synchrotron-light for Experimental Science and Applications in the Middle East) officially opened in 2017. It is the Middle East’s first major international research centre and is becoming an important push for the scientific, technical, and economic development of the Middle East. Thanks to this CBRL fellowship I was able, not only to conduct my own project but it’s allowed me a great opportunity to meet fellow scientists from this region of the world and establish new collaborations.

The opportunity to work with Cypriot archaeological remains and specifically, being able to learn how to work with Synchrotron radiation has been a fantastic experience. It allowed me to familiarise myself with new and highly advanced techniques, work as part of a vibrant and engaging research team and community and unravel stories of the Cypriot Prehistory. Although my fellowship is coming to an end, I am excited about the continuing and future projects with my colleagues and now also close friends from Cyprus, Jordan and other regions of the Levant.

Simone Lemmers is a Biological Anthropologist and Osteoarchaeologists. She holds a BA & MA in Archaeology and obtained her PhD from Durham University, studying the effect of physiological stress on teeth in primates. After her PhD, she returned to her passion for Archaeology by working on Bronze Age material as a postdoctoral researcher at Kent University. She is currently on a CBRL Visiting Fellowship at The Cyprus Institute, Nicosia, working with Dr Kirsi Lorentz

The views expressed by our authors on the CBRL blog are not necessarily endorsed by CBRL, but are commended as contributing to public debate.