By Dr Bahar Baser, University of Coventry and 2018 CBRL Pilot Study awardee.

The Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) held a referendum for independence in September 2017. Although the international community and the neighbouring countries in the region did not welcome this move, the Kurdistan Regional Government political authorities went ahead with their decision. The only country which showed open support to the KRI’s willingness to turn to popular vote to express its right for self-determination, was Israel. Kurds also welcomed this unexpected support. It was possible to detect Israeli flags among Kurdish ones at mass demonstrations in Kurdistan before and after the referendum. What was more interesting, however, was the gathering of Kurdish-origin Jews in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem to support Kurdistan’s independence. Their activism during this highly important political event made them all the more visible. Did they have a role in Israel’s support for Kurdistan?

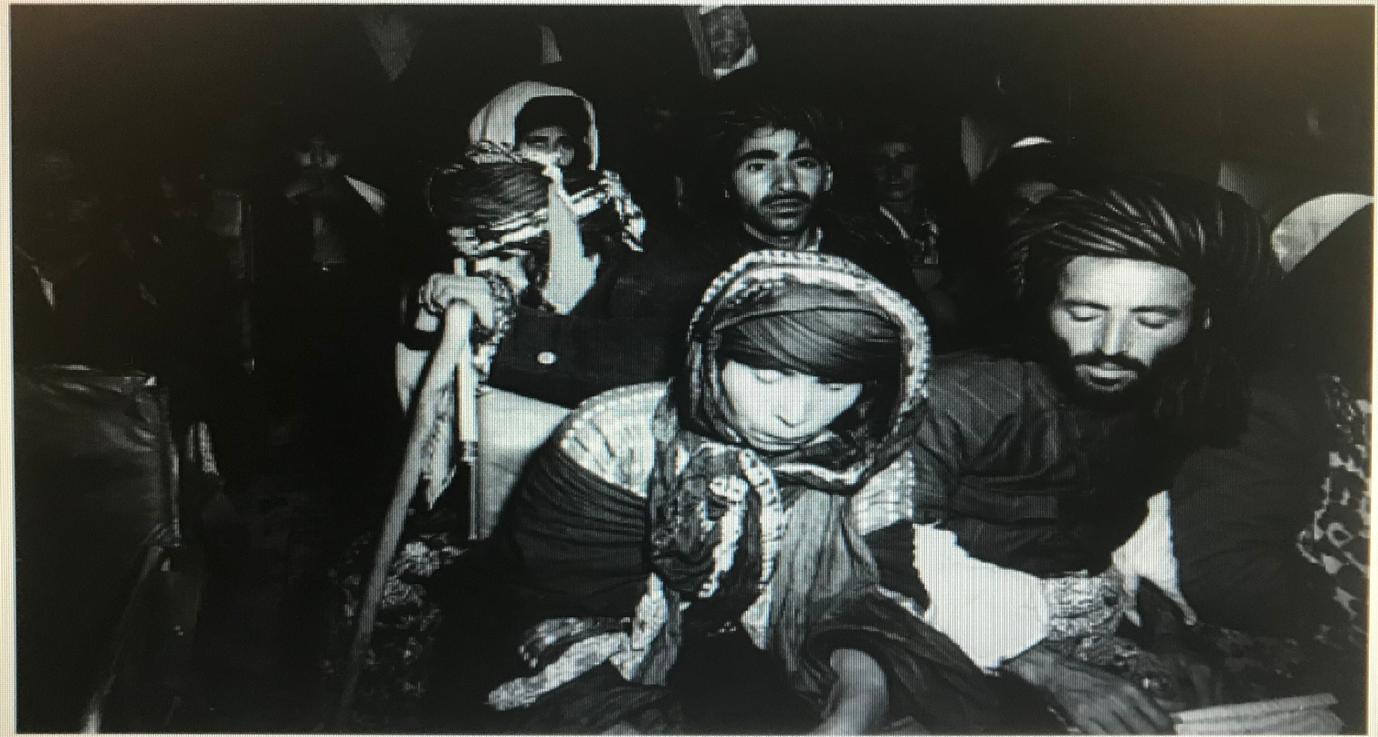

Thousands of Kurds were airlifted to Israel from Iraq in the early 1950s by Operation Ezra and Nehemiah after Baghdad briefly reversed its ban on Jewish emigration. More Jews moved to Israel during the following decades from other Kurdish areas in Iran, Turkey and Syria. The first generation and their descendants today constitute a sizeable community of more than 150,000.

My 2018 CBRL funded pilot project scrutinises the experience of Jews from Iraqi Kurdistan and aims to understand how these Kurds and their descendants are managing their multiple religious and ethnic identities while formulating a vibrant diaspora within Israel. I am specifically interested in political mobilization of this community in order to assess its leverage on Israel’s foreign policy decisions.

The importance of diaspora communities has long been recognized in different fields of social science. Scholars have extensively researched how diasporas affect developments in their homelands by sending remittances, investing in the homeland or by lobbying host states and supranational institutions. In a post-conflict setting, diaspora contributions become all the more vital as they can contribute to knowledge capital and knowledge transfer, capacity-building and investment.

The Kurdish diaspora is one of those influential diasporas that has significant visibility in the transnational space. As a result of conflicts in their countries of origin, Kurds have become dispersed throughout Europe and beyond. Many diaspora Kurds, along with their offspring, keep an attachment to their places of origin, and maintain a sense of belonging to Kurdistan. There is a vast literature which focuses on Kurdish diaspora mobilisation, lobbying and advocacy in host countries. These studies very effectively map Kurdish diaspora activism. However, they mostly focus on Kurds in Europe and create a somewhat Eurocentric literature on this issue.

Having studied diasporas and their political activism towards their homeland for more than ten years, I could see that there was a huge gap in the literature with regards to understanding diaspora mobilisation in the Global South. In the existing literature, diasporic identity formation is examined in light of current integration and opportunity structure debates in Europe, revolving around the issues of how different the Kurdish identity is from the host societies’ and how their attachments to their homeland affect their relationship with the host country. Political, social and economic remittances that the diaspora transfers back to the homeland is also understood within the Global North-South dualism. However, as Kurds are dispersed all around the world, there are sizeable Kurdish communities which constitute Kurdish diaspora(s) outside Europe, especially in the vicinity of the Kurdish homeland, such as Israel. But, imagine. Israel categorises Iraq (officially including the KRI region) as an enemy state. Can the Jewish Kurds still support Kurdistan despite this fact?

With this question in mind, I embarked on my CBRL funded fieldwork in Israel in October/November 2018. My aim was to explore the diasporic experiences of these communities whilst at the same time mapping their political leverage in Israeli and Kurdish politics. Most of my potential interviewees resided in Jerusalem and in surrounding towns and villages. With the help of my research assistant Nitzan Horesh, I reached out to Israeli-Kurdish organisations and their leaders as well as lay people who had origins in Iraqi Kurdistan. I interviewed fifteen community members as well as academics, journalists and bureaucrats in order to understand the diasporic practices of this community. I also visited the archives of the Diaspora Museum in Tel Aviv to better understand their perilous journey from Iraq to Israel and their settlement in the area surrounding Jerusalem, as the Mizrahi Jews.

My fieldwork immediately revealed that the political, social and economic structures of the Jewish Kurds in Israel are different from their fellow countrymen who reside in Europe. In Israel they are able to retain their Kurdish identity whilst adapting to their new homeland by identifying with the Jewish majority. They have formed various diaspora associations such as the Kurdistan-Israel Friendship association, National Organization of Jews from Kurdistan in Israel among others. Meanwhile Kurds who migrate to the Global North find themselves treated as “immigrants from the Middle East” or as “Muslim minorities”.

Although I have found traces of political activism, which are more ad-hoc than consistent, I have noticed that their attachment to the Kurdistan Region of Iraq is mostly cultural rather than political. For instance, community gatherings of folkloric dances and singing is still common and the traditional dish called “Kubbeh” is still extremely popular in this community. Without doubt, the diaspora community is heterogeneous and their levels of attachment vary. However, cultural and nostalgic connotations were easier to detect in our conversations rather than political references to the contemporary political issues in Kurdistan. One thing remained constant however, especially for the first-generation: They remember Kurdistan and their good memories there and they support Kurdistan’s independence.

I have presented my preliminary findings at conferences in Oxford and London and I plan to present them at the International Studies Association conference in Toronto in March. I have gathered archival material as well as qualitative interviews which will appear in my next book and articles. I thank the CBRL for this great opportunity.

Dr Bahar Baser is an Associate Professor at Coventry University. She is currently a Visiting Senior Fellow at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, University of Notre Dame where she is working on her book on Kurdish Diaspora Entrepreneurs and Statebuilding in Iraqi Kurdistan.

The views expressed by our authors on the CBRL blog are not necessarily endorsed by CBRL, but are commended as contributing to public debate.