By Dr Andrea Dolfini, CBRL Travel Grant recipient and Senior Lecturer in Later Prehistory at Newcastle University

Archaeologists have long wondered if the numerous metal daggers found in Middle Bronze Age ‘warrior burials’ from the Levant had ever been used in combat. Some suggest that they were meant to be weapons, while others stress that they may have been cast for the grave, perhaps to signify the warrior persona of the dead or elevated status within the community. The debate rages on and on, with no opinion prevailing over the other due to the lack of first-hand data on the use-history of these objects.

While discussing this issue with two colleagues from the University of Haifa, Professor Sariel Shalev and Dr Tal Kan-Cipor–Meron, I suggested that help might be handy in the guise of Metalwork Wear Analysis (MWA). This method enables the recognition, evaluation, and interpretation of the traces visible on prehistoric and historic copper-alloy objects (especially tools and weapons) by optical and electronic microscopy. MWA is a recently established, but fast developing, analytical method in archaeology. It gives insights into the life cycle of objects including their manufacture, uses, repairs, and post-discovery history, e.g. conservation and museum curation. As a leading MWA specialist, I have used the method to research hundreds of prehistoric metal tools and weapons from Europe, revealing often unexpected uses and life histories. However, I had never worked with eastern Mediterranean metals and was keen to see what the microscope could tell us about these objects.

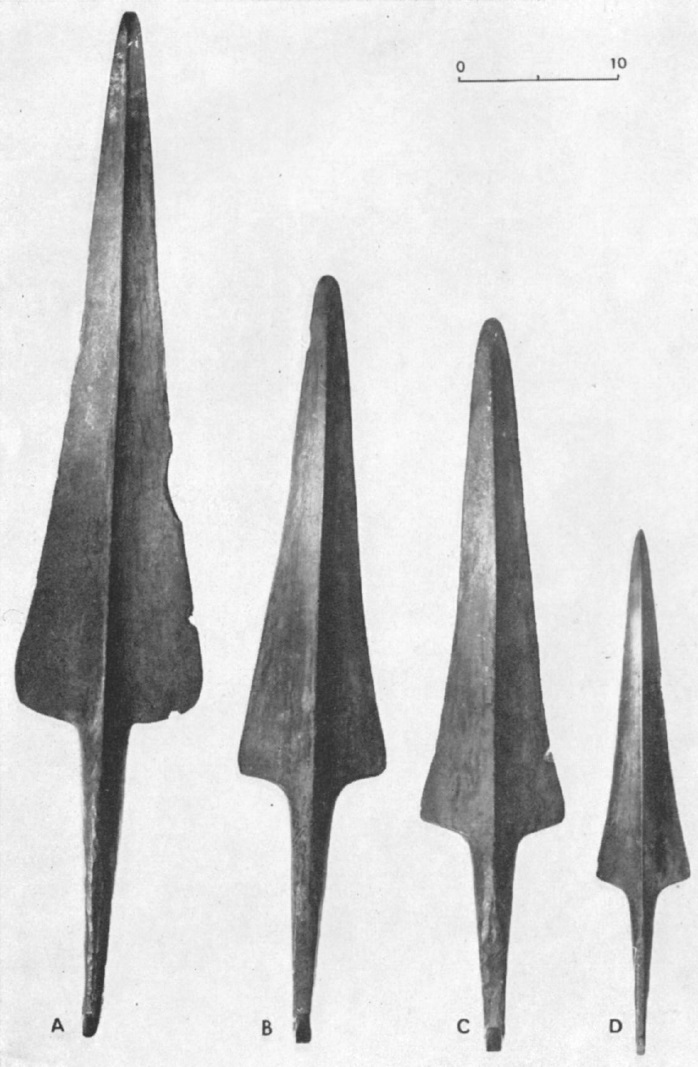

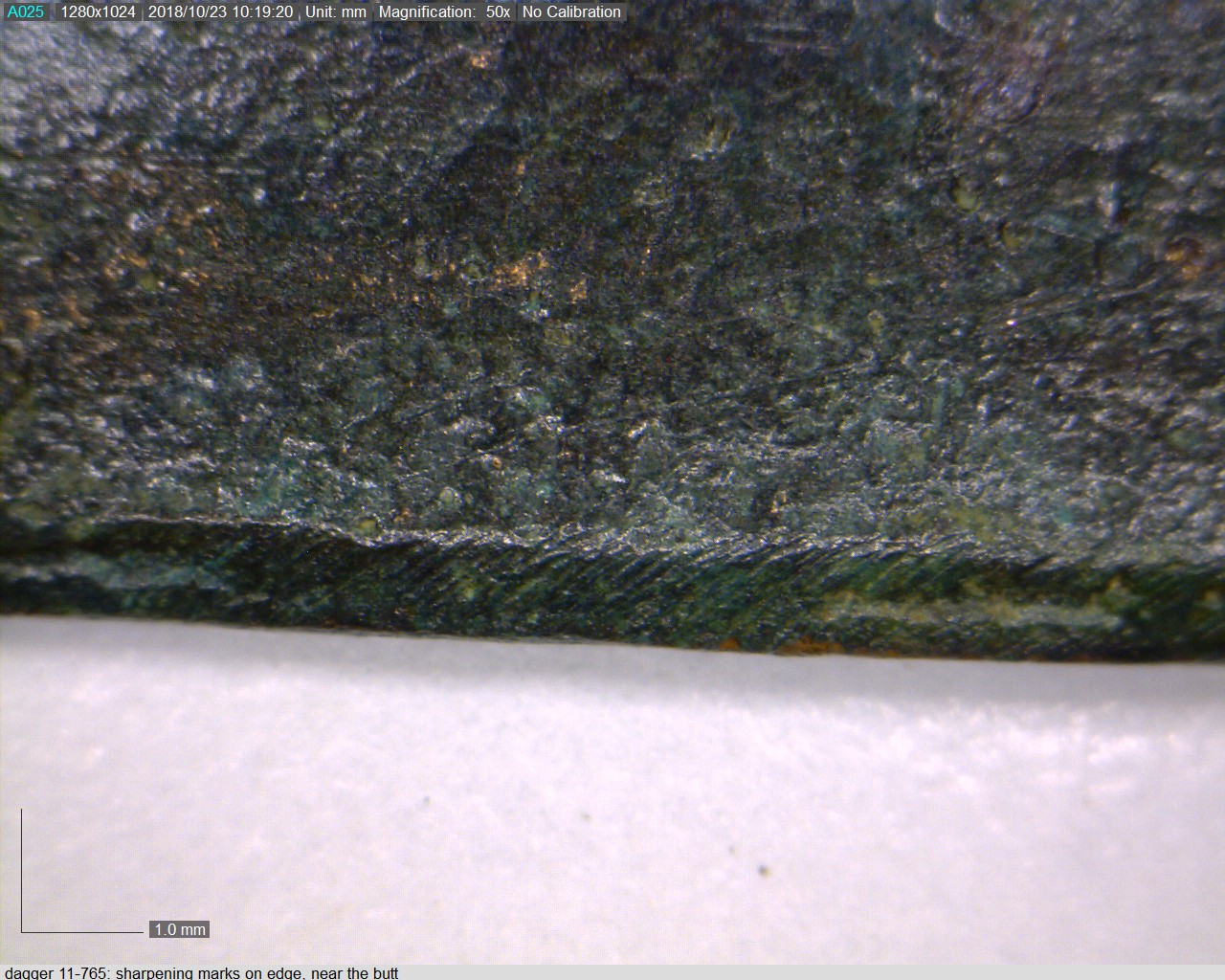

Thanks to a generous CBRL Travel Grant and the unwavering support of my Haifa hosts, I travelled to Israel in October 2018 to put 20 daggers from the Middle Bronze Age cemetery of Rishon LeZion to the microscope test. The site was selected because it had yielded two distinct dagger types, i.e. ribbed and decorated (type A; Fig. 1) and flat and undecorated (type B). The two dagger types, which also show unlike alloy compositions, are alleged to have different functions and life histories. The analysis was performed at the storerooms of the Israeli Antiquities Authority using a portable electronic microscope. It revealed that most daggers were highly corroded, with some being affected by invasive conservation treatments that made the analysis especially challenging. Due to these problems, as well as the small sample size, I was not able to answer the research question, although I did positively identify a few manufacturing and usage marks (Fig. 2). All the same, the trip was useful as it revealed idiosyncratic preservation problems (due to soil geology and the acidic grave environment) and conservation treatments that any future research on this material will have to consider.

I also examined other Bronze Age tools and weapons from the collections of the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, and the Hecht Museum, University of Haifa. These included objects from hoards, which showed better surface preservations than the metals from burials. Overall, the research visit revealed that: (a) useful data concerning the manufacturing and use-history of Bronze Age metals from the Levant can be gleaned through MWA, provided one works on a large sample of objects to control for surface preservation and conservation biases; and (b) hoarded objects tend to be better preserved than those from graves; they should therefore be targeted by future analysis.

A research team comprised of Professor Shalev, Dr Kan-Cipor–Meron, and myself was created at the end of the visit to take the project forwards. We are now working towards a British Academy-Leverhulme Trust small research grant application to analyse Early Bronze Age metals from the Kfar Monash Hoard. The hoard comprises several tools and weapons including near-unique, massive spearheads that might have been used as primitive swords or hybrid handheld weapons (Fig. 3). Intriguingly, these objects might reveal an alternative Mediterranean route towards the invention of the sword, which is thought to originate from Eastern Europe. This makes the project timely and, indeed, extremely exciting. Importantly, conservators will be involved in the project to gain a better understanding of the conservation methods utilised in Israel, and how they may affect wear visibility on metals. The forthcoming project will open up new research avenues and we cannot wait to see what the new analyses will tell us about Bronze Age warfare and society in the ancient Levant!

Further readings – Metalwork Wear analysis

Dolfini, A. 2011. The function of Chalcolithic metalwork in Italy: An assessment based on use-wear analysis. Journal of Archaeological Science 38(5): 1037-1049.

Dolfini, A. & R.J. Crellin. 2016. Metalwork wear analysis: The loss of innocence. Journal of Archaeological Science 66: 78-87.

Further readings – Rishon LeZion and Kfar Monash

Hestrin, R. & Tadmor, M. 1963. A hoard of tools and weapons from Kfar Monash. Israel Exploration Journal: 265-288.

Kan‐Cipor‐Meron, T., Shilstein, S., Levi, Y. and Shalev, S., 2018. A comparison study of Middle Bronze Age II daggers and their rivets as a tool for a better understanding of their production. Archaeometry 60(3): 535-553.

Andrea Dolfini is a Senior Lecturer in Later Prehistory at Newcastle University, England, UK. His research interests encompass the archaeology of early Italy and the Mediterranean, prehistoric metal technology, and the social dynamics of violence and warfare in prehistoric and preliterate societies. He is a leading specialist in the wear analysis of ancient copper-alloy objects, which he investigates by experimental archaeology and microscopic analysis.

The views expressed by our authors on the CBRL blog are not necessarily endorsed by CBRL, but are commended as contributing to public debate.