Reflecting on my experiences of fieldwork in Jordan as a doctoral student and CBRL Arabic scholar (2017), a phrase that came to mind was the anthropologist of Yemen Paul Dresch’s description of the ethnographic field as a ‘wilderness of mirrors’. Alongside nostalgia for a warm, intense and socially rich period of life, much of my experience seems encompassed in this evocative phrase, borrowed from Elliot. It evokes a place where any truth is ‘partial, contingent and ultimately elusive’, where intimacy and access are matters of degrees, and where areas of closeted sensitivity are important social facts as well as hindrances to collecting data. This phrase also gestures to ways in which Malinowskian fieldwork ideals come unstuck during contact between Euro-American scholarship and some Arabic-speaking social settings, under a weight of history, partial resemblances, and misunderstanding.

Sensations of disorientation, reflection and distortion are probably common to most anthropology students setting out on fieldwork; indeed they are reified as part of the rite of passage by which anthropologists are produced. Yet there is less overt discussion of how getting to know people and places better with time can serve to strengthen as well as lesson such feelings. In Jordan, where a well-established ‘hospitality niche’ has long developed for dealing with strangers and more recently for marking a type of national culture, this is especially true, as initial curiosity and social graces give way variously to bafflement, suspicion and wry amusement at the ethnographer’s somewhat absurd predicament, as well as perhaps some limited degree of shared confidence.

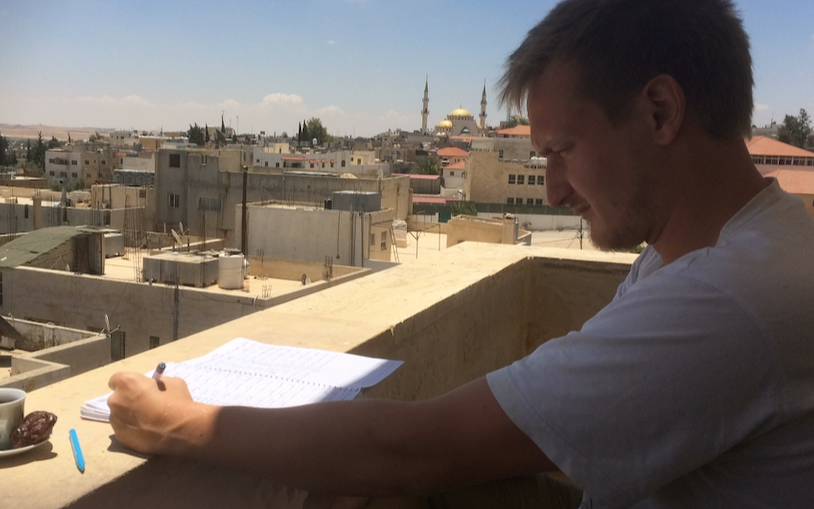

Fieldwork in Jordan was for me largely a pleasurable experience, full of warmth, graceful hosts, good company and food, and interesting conversations. It was also inherently awkward and uncomfortable, for reasons in part to do with my position as a kind of social mendicant, as well as with wider forces of history. For me, a student with shaky Arabic, and a great deal of uncertainty about not only the practicalities but also the purpose and even critical and ethical defensibility of my research and its conditions of possibility, arriving in Jordan was a welcoming but bewildering experience in ways beyond those discussed in ‘methods’ seminars.

It was not so much the everyday challenges of working out how to live and work in Jordan, which the wonderful community at CBRL Amman are well-versed in helping newcomers overcome. Linguistic and social confidence in these areas tends to develop quite quickly, if in my case, with continued clumsiness and an obliviousness to much nuance. My worst fear, of being ignored (due to linguistic or social ineptitude) was also misplaced. At least in the town and surrounding villages of Madaba, where I did most of my fieldwork, I found curious neighbours and acquaintances happy to talk and insistent on including me to some degree in social life, the more so when my ineptitude became apparent. It would have been difficult to remain isolated in such an environment, far more so than ‘at home’.

Rather, my biggest challenge often seemed to be to find a ‘voice’, and with it a research niche, that was original and legitimate according to the rules of my discipline, and more importantly would be recognised by my interlocutors as responsible and in good faith. I got to know various circles of mostly young men, who sometimes made use of putatively tribal and Bedouin identity categories, both online and through social practices centred around guestrooms and acts of patronage, in navigating a difficult socio-political environment. Early on, I saw the outline of an argument, around how such categories are not timeless social forces, but emergent and historically contingent, reproduced in new ways by changing political economies. Choosing to focus ethnographically on such themes leads into the heart of Dresch’s wilderness of mirrors. On the one hand, my interlocutors often instead wanted to focus on the ancientness of these things, deferred to a realm of culture and genealogy away from the political. On the other, I was confronted within weeks of joining by a discussion thread on the ‘Researching Jordan’ Facebook group about the most cliched research topics, of which tribes and kinship topped the list, and a more general sense that even when partially ameliorated through using Arabic terms and taking account of changing historical contexts, talk of tribes was to some inevitably regressive and orientalist. I haven’t space to treat either issue here, but suffice to say, I’ve yet to entirely find my own way through this particular wilderness of mirrors.

The often-productive strangeness of fieldwork, as much a matter of positionality as of any ‘culture shock’, is followed by abrupt return and introspection. The process of emersion and then semi-severance casts a whiff of instrumentality over the relationships being put into the text. Asking some interlocutors to read and approve quotes and paragraphs, and to discuss what I could and couldn’t use, involved deeply awkward conversations, but so too did discussing the differences in our lives and experiences of the pandemic. As I experienced this process, I was aware not of a resolving picture, but of vast new and unlooked-for questions emerging, what Strathern has termed the ‘fractal’ dimension of the social.

This disorientating realm of partial reflections and endless depth is no longer one which is neatly cut off when fieldwork ends and ‘writing up’ begins. These days, fieldworkers find themselves partially and intermittently engaged with their interlocutors via social media and video calls in a kind of semi-permanent afterlife, made especially poignant in the last year by the impossibility of travel and in-person interaction. Intellectually and emotionally, such afterlives are at once significant and unsatisfying, allowing often stilted and awkward, occasionally poignant, but always distorted and curated, access to other lives and worlds, so that fieldwork becomes another arena full of latent presences and absences and only partially severed connections, of the sort that populate much of our online lives. Through this strange window, I reflected on the partiality, briefness, and limits of fieldwork, as research and as ethical engagement.

As much as the social and sensual texture of daily life, (the to-and-fro of friendships and visits, the sounds of spoken Arabic and of the jingles of gas vans, the metonymic smells and tastes of coffee and food) such uncomfortable sensations are an integral part of my experience of fieldwork in Jordan. The uncomfortableness grows rather than diminishes with knowledge, distance, and time, especially during these difficult times, and can serve methodologically as a lens through which to reflect on the politics of research more broadly. Anthropologists have (or should have) long lost their epistemological innocence, but where orientalism, settler colonialism, sustained and ongoing economic and geopolitical trauma, and a legacy of tribalising and othering (mis)reading combine, uncomfortable honesty is especially important. Fieldwork, like being a guest, is not, and should not be, an entirely easeful or comfortable experience.

About the author

Frederick Wojnarowski completed his PhD in social anthropology at the University of Cambridge in 2021, where he is now a Postdoctoral Affiliate. He is interested in the political and economic anthropology of Jordan and the wider Levant, especially questions of history, identity categories and protest. He was a CBRL Arabic Scholar at the BIA in 2017 during his PhD fieldwork, mostly based in Madaba and its surrounding villages. His PhD thesis was entitled Unsettling Times: land, political economy and protest in the Bedouin villages of central Jordan.

The views expressed by our authors on the CBRL blog are not necessarily endorsed by CBRL, but are commended as contributing to public debate.