By Alison McQuitty

Excavation reports are hard work. Hard work to write and all too often hard work to read and use. We persevere because they comprise the vital primary evidence from which more widely applicable narratives and interpretations emerge. Khirbat Faris: rural settlement, continuity and change in southern Jordan is no exception. This volume, published last spring, describes and analyses the stratigraphy, architecture and small-finds from a British Institute at Amman for Archaeology and History (BIAAH) - later CBRL - funded and sponsored excavation carried out in the late 1980s/early 1990s, focusing on the rural landscape in Jordan (Figure 1). This landscape and its character is one of the richest parts of the country’s heritage.

I first visited the site in 1986 with Jeremy Johns (Director of the Khalili Research Centre; Professor of the Art and Archaeology of the Islamic Mediterranean, the Oriental Institute, University of Oxford) who was exploring Jordan with a view to starting a project that looked at the then comparatively unknown archaeology of the mediaeval period in the country. We hiked through Petra in the rain; tinkered with the temperamental BIAAH Land Rover; shivered in the Karak resthouse andthen came to Khirbat Faris on a positively balmy day when the gentle hills of the Karak Plateau were flushed with the first green of spring. And so a project was born (Figure 2).

I was particularly excited that my previous research into the everyday life of villages and their architecture could be extended back in time (Figure 3).

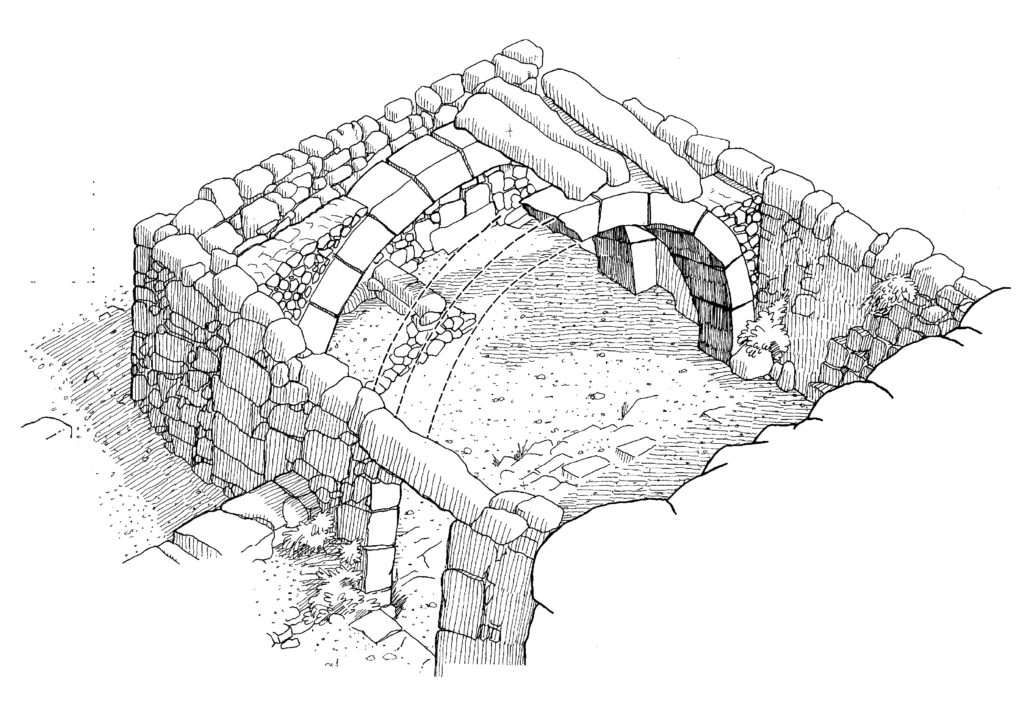

I had studied the vernacular architecture of northern Jordan which stretched back to the early 20th century and my first research in Jordan was on bread ovens – commonly found on archaeological sites but at that time seldom considered in detail. I had an abiding interest in the landscape – the way in which multiple groups of people used the same environment in different but complementary ways (Figure 4) – and in the structures of that landscape be they springs, water mills, tracks or lime kilns.

Underpinning these questions was my experience as a field archaeologist and a desire to confirm that excavation recording methods familiar in Britain at that time were appropriate and beneficial to the clarity of interpretation of archaeological excavations elsewhere. This project and the other scholars and professionals involved – from the disciplines of anthropology to archaeobotany, from history to ceramics – promised that my research interests, plus those of others involved, would be met.

Some of those voices are quoted below and, as anyone who has been involved in a field project will recognise, often the reflections that persist are not to do with research aims but are still experiences that can have a long-lasting impact on future career and life choices. Such memories are seldom recorded in formal literature.

Chantelle Hoppe remarks: “I was a tender 22-year-old when I first turned up at the Faris excavation. It was my first go at independent travel. It felt very exciting – to be going to the Middle East on my own. We were a mix of people with different backgrounds, from museums to students (I was an MSc student from Sheffield University at the time – studying Environmental Archaeology with a specialism in archaeobotany), to our very capable cook, Fridtjof Eykenduyn – who introduced me to the delights of super spicy food! We lived in a local community and worked alongside Jordanians. I have never experienced such friendly and hospitable people as my time in the Middle East. I am now about to turn 50 and those formative memories have been a great source of anecdotes as I’ve gone through life and are much treasured memories.”

Rob Falkner, a ceramicist, recalls the less archaeological aspects: “Trying to remember bits and pieces from a life in archaeology 30 years ago, gave me quite a surprise. I could still remember the pottery, the sites, the friendships and a host of stories, but surprisingly food was quite high on the list. Seasons at Faris have now all blended in to one, so chronology may be a little out, (what’s strange about that in archaeology?) but food again rears its head. Top of the list must be Maltese Joe’s sumptuous feast. A man of many and varied skills including film production, animal husbandry and slaughter, and cooking. His pasta in rabbit sauce followed by rabbit casserole was a triumph. Now I know why I weigh so much.”

Jim Mason, a potter, remembers the schedule: “It was a gruelling schedule. The mornings were cold, then pleasant by 08.00, and hot for the rest of the day. And I thought potters worked fairly hard. The routine was broadly: up at 05.00, leave at 05.30, start work at 06.00, work till first breakfast at 08.00, work until second breakfast at 10.30, work from 11.00 until 14.00 or 15.00, get back, have a beer, sleep until about 17.00, shower, more beer, eat around 18.00 or 19.00, drink, bed at 20.00 or 21.00. Continue for six weeks.”

Andrew Petersen (Director of Research in Islamic Archaeology, University of Wales Trinity Saint David) writes of the bright spring sunshine and green grass swaying in the wind, and the chants of the workmen heaving out huge stone rafters (Figure 5). From the dig house he remembers the view and pleasant evenings watching the sunset over the Jordan Valley. He also remembers one cold evening listening to the news from China as the Tiananmen Square massacre unfolded.

The project and its results did not betray my initial enthusiasm. Our results cover the periods from the 13th century BC to the present day, with a focus on the architecture and material culture of Nabatean, Late Antique, Islamic and modern centuries (Figures 6 and 7), while current themes of Islamic archaeology are also discussed in the volume.

Alison McQuitty is an archaeologist with a particular interest in vernacular architecture, rural settlement, and landscape in Jordan during the 6th – 20th centuries A.D. She has a B.A. in European Archaeology from the University of Durham and an M.A. in Middle Eastern Studies from SOAS, University of London. She co-directed the excavations at Khirbat Faris, Southern Jordan with Professor Jeremy Johns, Director of the Khalili Research Centre, University of Oxford. Alison’s interests have developed in diverse ways ranging from leading the refurbishment of a local Jordanian museum to lecturing on heritage management to organising bespoke tours to the Middle East and North Africa. Through all of these activities has run the thread of Alison’s passion for encouraging public engagement with the heritage and landscape.

Alison McQuitty is an archaeologist with a particular interest in vernacular architecture, rural settlement, and landscape in Jordan during the 6th – 20th centuries A.D. She has a B.A. in European Archaeology from the University of Durham and an M.A. in Middle Eastern Studies from SOAS, University of London. She co-directed the excavations at Khirbat Faris, Southern Jordan with Professor Jeremy Johns, Director of the Khalili Research Centre, University of Oxford. Alison’s interests have developed in diverse ways ranging from leading the refurbishment of a local Jordanian museum to lecturing on heritage management to organising bespoke tours to the Middle East and North Africa. Through all of these activities has run the thread of Alison’s passion for encouraging public engagement with the heritage and landscape.

The views expressed by our authors on the CBRL blog are not necessarily endorsed by CBRL, but are commended as contributing to public debate.