By Anne Irfan, winner of Contemporary Levant’s best paper award of 2020 and Departmental Lecturer in Forced Migration at the University of Oxford’s Refugee Studies Centre.

The Palestinians’ struggle for statehood has been core to the politics of their seven decades of dispossession. As Palestinian refugees have contested the conditions of their exile since 1948, their national movement has variously sought recognition as a state-in-exile, a state-in-waiting, or a liberation movement transcending nation-state boundaries. Over the final decades of the 20th century, the Palestinian campaign for statehood was pursued most definitively by the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO), formally recognised by the UN in 1974 as the Palestinians’ representative body. The PLO sought to act as the de facto Palestinian government on the world stage, chiefly by representing the Palestinians in international negotiations. Since the mid-1990s, parts of the PLO have been subsumed under the Palestinian Authority (PA), which was created as a supposedly interim arrangement pending Palestinian statehood. Neither the PLO nor the PA today comprise a fully-fledged Palestinian state, despite their attempts to function as such.

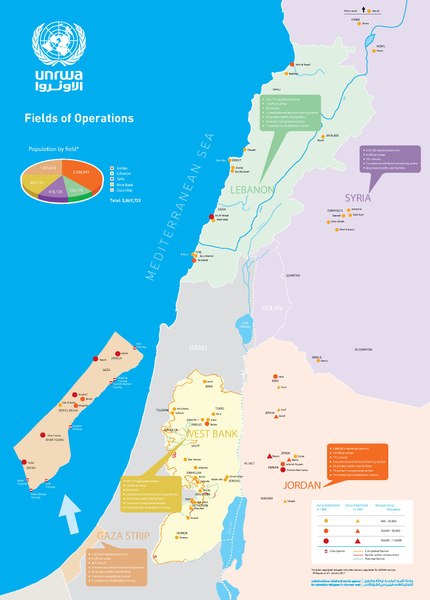

Yet these entities are not the only ‘surrogate states’ for Palestinians. My research into Palestinian refugee history, funded in part by a CBRL travel grant, focuses on the role of another organisation: the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA). As the UN refugee regime’s primary instrument in the Palestinian context, UNRWA has provided essential services to registered Palestinian refugees in the Levanti since it began operations in 1950. As well as delivering large-scale healthcare and education programmes, UNRWA provides some municipal services in the Palestinian refugee camps, and issues ID documents to registered refugees.

These functions have led many observers to describe UNRWA as fulfilling a quasi-governmental or even a quasi-state role for the stateless Palestinians. Riccardo Bocco has dubbed it ‘the Blue State’, in reference to the UN’s distinctive branding colour, while Sari Hanafi describes UNRWA as a ‘phantom sovereign’. In my research, I observed a widespread tendency for Palestinian refugees to conceive of UNRWA as a poor substitute for the state to which they are entitled, and even an inadequate compensation prize created by the UN in lieu of the former. This conceptualisation has had a direct impact on the relationship between UNRWA and the Palestinian refugee communities it serves; my research shows how the latter have regularly approached the Agency’s services as entitlements, not charity.

Over the course of my research, I became increasingly aware of the importance of another relationship in Palestinian refugee history: that between the ‘surrogate states’ themselves, UNRWA and the PLO. As the latter rose to prominence in the refugee camps after the 1967 War, it increasingly came into contact with UNRWA, the UN agency that provided essential services therein. Their relationship, formalised after the UN recognised the PLO in 1974, was inherently complex. Some of their objectives were aligned; both organisations provided services in the Palestinian refugee camps, and may even have relieved some of the pressure on each other in doing so.

Yet in other regards, the two entities were firmly at odds with one another. Most critically, UNRWA’s UN status committed it to political neutrality, while the PLO encouraged overt politicisation in the camps at every opportunity. This resulted in increasing tensions when the PLO’s power in the camps rose significantly in the 1970s, particularly in Lebanon. Prior to its exile from the country in 1982, the PLO was determined to position itself as the Palestinian government-in-exile; UNRWA had no such desire – quite the opposite – but its resources and authority as a UN body meant that the PLO could never entirely usurp its place in the camps. The resulting overlap, tensions, and ultimate inadequacies meant that Palestinian refugees ended up with a surfeit of pseudo-states amidst an absence of real statehood.

Why does any of this matter? While the most obvious significance of my research concerns Palestinian political history, it also speaks to a number of broader themes that transcend the Palestinian case alone. The roles of the PLO and UNRWA both underline and complicate conventional understandings of statehood, speaking to bigger discussions about what this concept really means in a post-colonial context. Their tensions also highlight the inherently problematic nature of protracted statelessness in a global system grounded in nation-state normativity – problems that unfortunately look set to continue for the Palestinians as they enter their eighth decade of statelessness.

For more on this subject, read Anne Irfan’s full article, ‘Palestine at the UN: The PLO and UNRWA in the 1970s’, in the latest edition of Contemporary Levant.

Anne Irfan is Departmental Lecturer in Forced Migration at the University of Oxford’s Refugee Studies Centre. She is PI on the British Academy-funded research project, ‘Borders, global governance and the refugee, 1947-51’. Her work has been published in Journal of Palestine Studies, Journal of Refugee Studies and Jerusalem Quarterly; she was awarded the 2020 Contemporary Levant Best Paper prize for her piece, ‘Petitioning for Palestine: Refugee appeals to international authorities’. Dr Irfan is currently completing a book on the political history of the UN regime in the Palestinian refugee camps.

Anne Irfan is Departmental Lecturer in Forced Migration at the University of Oxford’s Refugee Studies Centre. She is PI on the British Academy-funded research project, ‘Borders, global governance and the refugee, 1947-51’. Her work has been published in Journal of Palestine Studies, Journal of Refugee Studies and Jerusalem Quarterly; she was awarded the 2020 Contemporary Levant Best Paper prize for her piece, ‘Petitioning for Palestine: Refugee appeals to international authorities’. Dr Irfan is currently completing a book on the political history of the UN regime in the Palestinian refugee camps.

The views expressed by our authors in the CBRL blog are not necessarily endorsed by CBRL, but are commended as contributing to public debate.