For five nights across May, as the world reflected on the 75th anniversary of al-Nakba, ten Palestinians in Amman joined me for the workshop series “The Material Witness” at Darat al Funun. The inspiration for the workshop emerged from my doctoral research project which explores the question: “What is the role of the house in the creation and performance of “Palestine” among Palestinian exiles living in Jordan and Lebanon?”. My aim was to use objects from within participants’ homes – referred to as material witnesses of Palestinian exile – to inspire them to narrate their own stories. During these days, we met in the same 25m2 space in Darat al Funun which had been turned into a blank canvas for us to mark. It is one of the tiresome parts of the Palestine case, that Palestinians still must assert their existence and presence. Therefore, it felt restitutive through the act of physically marking the walls not only with the material witnesses’ journeys of exile but additionally tracing the development and evolvement of their Palestinian presence.

To Play

It was in the first workshop during discussions of what does “heritage” mean, that one participant said “play”. She went on to describe how she felt there’s a need to think about how we play with heritage and make it relevant to contemporary Palestine. An initial disruption had taken place – as if the participant had given permission for the others to join her in this “playing”. As a researcher, interested in methodology as well as empirical findings, the workshop series was for me, an opportunity to experiment with such playing and methodology and to see how the experience generates stories which differ from the more traditional approach of conducting individual interviews across Amman. Likewise, it was inspiring to be in a setting which explores questions of ownership of research and the surrounding dialogue. The stories I research are not my stories and never will be. Therefore, how is it to work with a cultural heritage space in Amman, so that the findings and stories stay within the city. Such a workshop, I felt did not just allow for the collective to play and disrupt ideas regarding what it means to be a Palestinian in exile in Amman today, but methodologically for me to play and have my own research ideas disrupted – which in the first year of the PhD programme is, I feel, a must.

The objects that found their way to our 25m2 blank canvas, were I believe, illustrations of how the “fixed [collective] objects” of Palestinian heritage are shifting. Where the “blank” space became an important tool to tease out the important moments of “playing” and “disrupting” of meta-narratives surrounding Palestinian identity on three levels: the local, the national and the transnational. The room was graced with a ma’amoul cutter, a straw tray, a shemagh, and clay pot to name just a few. By focusing on the individual objects, and all that its story revealed, the everyday inner conflicts on identity and heritage emerged.

A clay pot from Gaza

A clay pot from Gaza

During our second workshop, the group were mapping both real and imagined journeys of their material witness, visualising the object’s displacement. Real journeys – journeys that the narrators had themselves been on with the material objects – were marked in yellow string and imagined journeys -journeys known through family stories- in red. The visualisation took place across two walls with one wall showcasing journeys to Amman, whilst the second solely had a map of Amman as a way in which to in detail see where these material witnesses of Palestinian exile were now within the city.

Staring at the maps of Palestine and Jordan, and the post-it notes that signalled that we needed to add maps of Lebanon and the Gulf. A participant turned to the group “Can we add the future to the map?”.

What if?

It was as if the room had taken a large exhalation. Something had lifted, and the collective started to postulate about the idea of “what if”. Whilst some of the collective added string back from Amman to where the objects’ story had begun; others put pins to cities such as Sufud because when exploring Palestine through google maps it looked beautiful. Another placed a pin in Damascus, not because of any connection per se but because if these objects were free to cross any border or boundary, then why not. Strikingly, the very interlocutor who asked about inclusion the future added no pin. For her, the notion of the future was something impossible to comprehend in that moment.

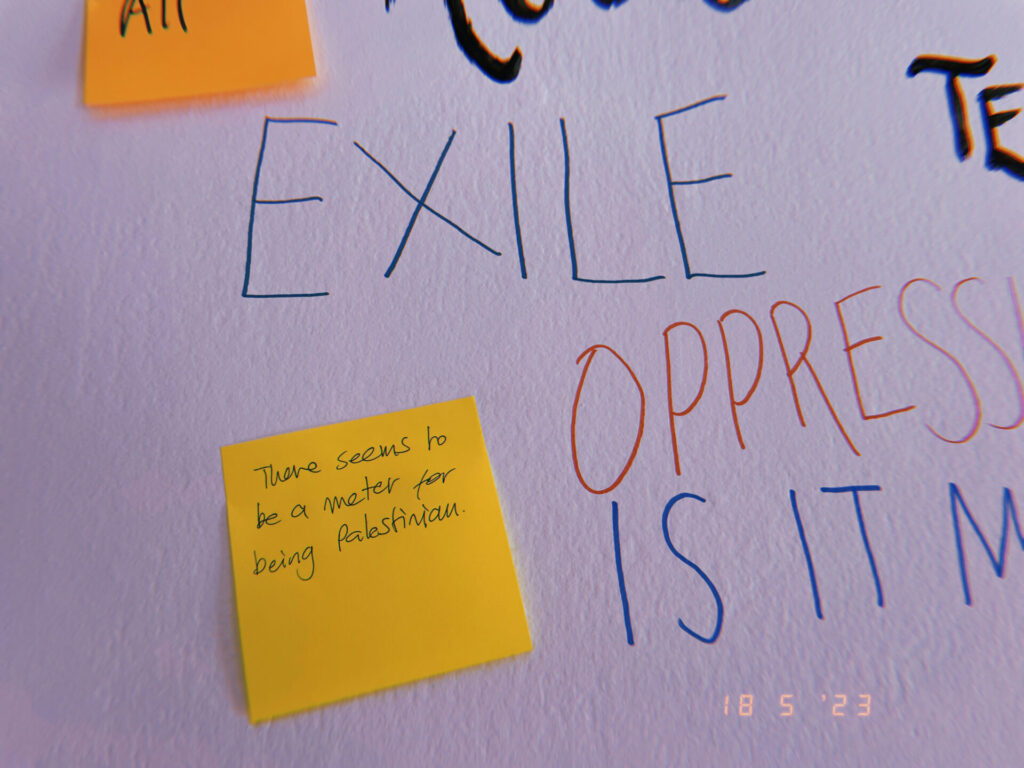

Whilst the objects already provided a more personal opportunity to tell their Palestinian story, the inclusion of the future opened a space for individual creation. Discussions emerged over feelings of “censorship” when thinking about their story of being Palestinian in Amman and in the wider transnational context. “What if I don’t want al-Nakba to be the start of my story?” “What if my desire is to relate to contemporary Palestine rather than Al Nakba solely?”. One participant simply wrote on the wall “there seems to be a meter for being Palestinian”.

A dialogue consequently ensued regarding the worries many of the collective had about “being Palestinian enough”. Adamant that “being Palestinian” cannot be linked to suffering and that it would be dangerous for it to be so, the collective had brought to the forefront one of the continuous internal conflicts of being Palestinian.

Reflecting on Disruption

In a post workshop conversation with one of the participants, I saw the way in which the workshop had caused disruption. Disruption in the sense in which it can add depth, nuance, and complexity by causing an interruption to one’s foundation – bringing a new layer to it. Sat with iced tea, she told me how in the aftermath of the workshop felt more Palestinian than before, she felt free from thinking that her Palestinian identity had to be connected to the famous Palestinian stories. There was a sense in which she described an emancipation from the dominant cultural production of Palestine.

These objects not only become part of an extended archive of Palestine but when these objects are invoked as material witnesses who are allowed to speak for themselves, what emerges is a space in which alternative dynamics of Palestinian heritage and memory-making, identity, and social forgetting of the past can be (re-)constructed and (re-)negotiated.

The views expressed by our authors on the CBRL blog are not necessarily endorsed by CBRL but are commended as contributing to public debate.

Eleri Connick is a British doctoral candidate at the University of Amsterdam in the School for Heritage, Memory, and Material Culture. She was the PhD Fellow at Darat al Funun (Amman) February 2023 – July 2023 and a ZEIT-Stiftung Ebelin und Gerd Bucerius Beyond Borders Start-up scholar in 2022/23. Her doctoral project titled: “The Palestinian House (al-bayt): The Materiality of Exile in Jordan and Lebanon” explores two specific cities: Amman and Tripoli respectively.